Illinois Theatre

1600 Second Avenue

Rock Island never lacked culture. That was demonstrated in 1901 when a plan to build a new theatre that had been promoted by the Rock Island Club and the Argus finally came to fruition with the hiring of George H. Johnston of St. Louis. But before anything could be built, money had to be raised. In an innovative twist, Mr. Johnston came up with a scheme to sell opening night tickets well before the proposed theatre’s site was even selected. The premium priced tickets, from $10 for a single seat to $100 for a box, sold out almost immediately. By March 8, 1901, $10,000 had been raised. Construction could begin.

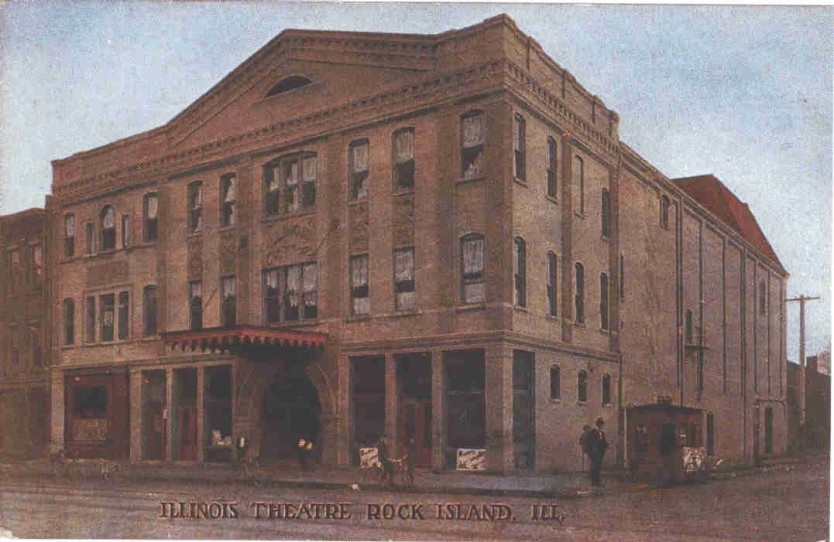

To keep interest high, the Argus announced a competition to name the new theatre. Names were submitted and voted upon by the public. Among those proposed were Empire, Century, Excelsior, Knickerbocker, Occidental, Island City, and, the winner, the Illinois Theatre. Then a parcel of land at the southeast corner of 16th Street and Second Avenue, catty-corner from the 1877 Harper Opera House was chosen. Mr. Johnston’s plans and specifications for a three-story stone front theatre that would hold shops on the first floor were quickly approved. Construction proceeded faster than we can imagine today, so that the building was completed in six months, less than a year after those phantom tickets were sold.

Opening night on December 26, 1901, attended by 1400, was deemed “quite the society event of the season.” The Argus reported the event in detail, even listing the occupants of the eight boxes. The interior colors and the plastic – probably molded– designs on the walls, ceiling and proscenium were praised. The curtain was called “a dream.” Ushers were attired in evening dress and the “bon bon boys” wore uniforms. An opening speech by T. J. Medill, president of the Rock Island Club, lauded all who made the theatre possible.

Unfortunately, the evening’s play was panned. And in an even more disconcerting comment, the news report stated that the large audience gave one of the “severest tests in regards to the weight the balcony and gallery will bear.” Fortunately, no evidence of structural weakness was observed. But theatre safety would be an issue in the near future.

Almost exactly two years after the Illinois’ opening, a disaster occurred in a theatre that had only a slightly larger seating capacity. The brand new Iroquois Theatre in Chicago caught fire when a spotlight shorted-out during a production, creating sparks that ignited scenery on the stage. Over 600 died in what was determined to be a series of errors in both design and use.

As a result of that fire, theatre reforms were instituted across the country. Such things as fireproof scenery, outward opening doors, and illuminated exit signs were required. This affected the Illinois Theatre as well, which was closed for a time to make necessary improvements. Among the changes was a new asbestos curtain, which was run up and down before every performance to assure patrons that it worked. (The Iroquois had an asbestos curtain, but it got caught on scenery and wouldn’t descend, allowing the fire to spread to the audience.) To eliminate any necessity for jumping, two stairways wide enough to accommodate patrons three abreast, were extended from the gallery and balcony all the way to the sidewalk on the west. Seven new standpipes with 750 feet of hose were also added, as were doors in the stage roof to vent a possible fire.

The Illinois Theatre was a success. Its stage hosted traveling troupes of all kinds, from vaudeville and minstrel shows to wrestling competitions to serious plays and even higher brow opera singers. Local groups such as the Rock Island Choral Union held concerts and plays there. Talent shows were a hit, too.

Then another disaster of sorts – movies. Although the theatre could be used for silent movies, the immediate popularity of celluloid meant the demise of live theatre. By 1920, the Illinois was used only occasionally. About that time, the exterior was remodeled, eliminating the peaked gable at the front and changing its appearance to what we see today on the upper stories. Further construction was announced in 1929, when the theatre was converted to a Montgomery Wards Department Store.

Contractor Sam Weisman did that remodeling using plans drawn by architects Benjamin Horn & Rudolph Sandberg. Partitions on the first floor were removed and the ceiling was raised to accommodate a new mezzanine. The basement was excavated further to hold additional sales space and the storefront was remodeled to incorporate two prominent entrances with large show windows. Although the building we see now doesn’t bear much resemblance to the postcard, it is still considered historic but based on its 1929 rather than its 1901 appearance.

After Wards moved to the Best Building, the former theatre became home to a series of furniture stores. For over thirty years, Hyman’s Furniture, under the caring ownership of Stanley Goldman, has been the anchor for this historic old former theatre as he kept the lights on downtown. In 2006, Mr. Goldman consolidated his furniture stores in the former McCabe’s building and donated the old Illinois Theatre to the YWCA.

This article, by Diane Oestreich, is slightly modified from the original, which appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on June 8, 2003.

February 2013