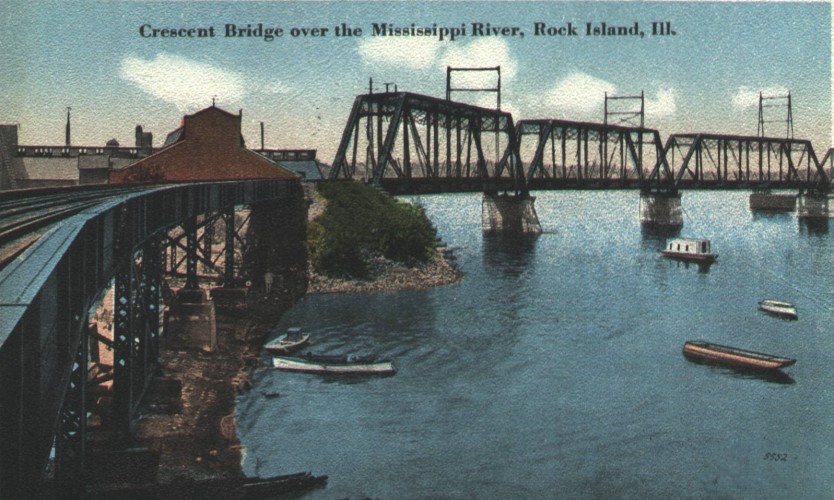

Crescent Bridge

Foot of 7th Street

Did you ever wonder how the Crescent Bridge got its name? Or do you even know where the Crescent Bridge is? For years it was hidden behind Rock Island’s levee near 7th Street and was best seen from the river or from the Centennial Bridge. Since it’s usually seen with the draw span open and no train in sight, you may have speculated whether it was a functional bridge any more.

But now that Rock Island’s riverfront path is open all the way to Sunset Park, lots of us see the Crescent Bridge as we approach from either side and then dip right under it to continue our walk or bike ride. So take a look at the postcard and learn a little bit more about this historic bridge.

First of all, to keep you in suspense no longer, the Crescent Bridge was so named simply because it forms a crescent. Trains can’t turn sharp corners so it’s necessary to create a relatively large track radius to enable them to change directions. Since the tracks run parallel to the river on both sides, a large curve was needed on either side of the bridge. Behold – the crescent was formed.

The century-old bridge was built and owned by the Davenport, Rock Island, & Northwestern Railroad, commonly called the DRI Line. The company was created primarily to pickup and deliver goods to local factories, but it also offered some passenger service. Approaching from the east in Rock Island, then crossing the river, the tracks turn back toward the east on the Iowa side. The original route went only from Clinton to Davenport then across the bridge to Rock Island and Moline.

A formal welcome and official opening for the Crescent Bridge occurred on January 6, 1900, when a special train arrived here from Clinton bearing railroad officials, dignitaries, and reporters. All along its route cities and towns welcomed it with the sound of bells and factory whistles. In Davenport, a cannon was fired in greeting.

The original train schedule showed the DRI Line making three trips a day back and forth between Rock Island and Clinton. Connections to other railroads could also be made. In a speech at the Rock Island Club during the grand opening, John Lambert, DRI Line vice president, expressed his vision for the future: Grain from the northwest would move by rail from this area to New Orleans. On the return trip, southern cotton would fill the trains. And then the Quad Cities would develop their immense potential for waterpower and build mills to process the raw cotton. Unfortunately, the dams that were necessary for waterpower were instead created for navigation, allowing barge transport to replace that of railroads for many items.

This undated early postcard shows the bridge looking like it does today. Iron trestlework supports the approach to the bridge at the water’s edge. Today that approach is on solid land many yards inland. In the background, the buildings of Rock Island Plow Works are visible. In the foreground, there’s a small cove, perhaps created by the bridge abutment, which appears quite popular for small boaters. Just a bit farther upriver, near the foot of 9th Street, Rock Island even had a popular riverfront bathing beach in the 1920s. Over the decades, first the lock and dam and later the levee have altered the appearance of the river’s edge.

Technical details of the bridge? Only one track wide, it was designed by C. F. Loweth and built by the Phoenix Bridge Company. There are seven fixed spans of varying lengths from 200 to 365 feet, and a draw span of 442 feet, for a total length of 2,325 feet. The beautifully shaped draw span is 70 feet high and was operated with Westinghouse equipment. The bridge landed on Willow Island in Davenport and went from there to the main shore over a steel trestle.

The Phoenix Bridge Company evolved from a small nail factory begun in 1812 in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. By 1841, now the Phoenix Iron Company, it was refining and rolling pig iron. In the 1850s, the company began making structural iron and invented the “Phoenix Column,” a hollow wrought iron column formed of sections bolted together. It was extraordinarily strong, so strong that the columns began to be used in bridges.

The Phoenix Bridge Company was created as a subsidiary of Phoenix Iron Works. The company first created “catalogue” bridges – kits that could be assembled from prefabricated parts. Soon it expanded into building very large and impressive bridges. Although they were responsible for a surprising number of failed bridges near the turn of the century, the company was nonetheless very successful until the 1920s, when concrete mostly replaced iron in bridges. It remained in business until 1962, making relatively nondescript bridges.

And yes, the Crescent Bridge is still used today. The former DRI Line is now part of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad. Only half a dozen or so trains pass over the bridge each day. That’s why the draw span is usually open – there are more boats and barges than trains. The bridge also has to be closed for the tender in the little house at the center of the draw span to get to and from work.

So take a walk or bike ride on the riverfront path and look at the bridge. Notice the different shapes of the spans and the graceful geometry of the draw span. And be sure to wave to the bridge tender – he’s always home.

This article, by Diane Oestreich, is slightly modified from the original that appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on September 9, 2001.

February 2013